This blog post was originally posted on the Davis Humanities Institute’s website, and is being cross-posted with the permission of the author.

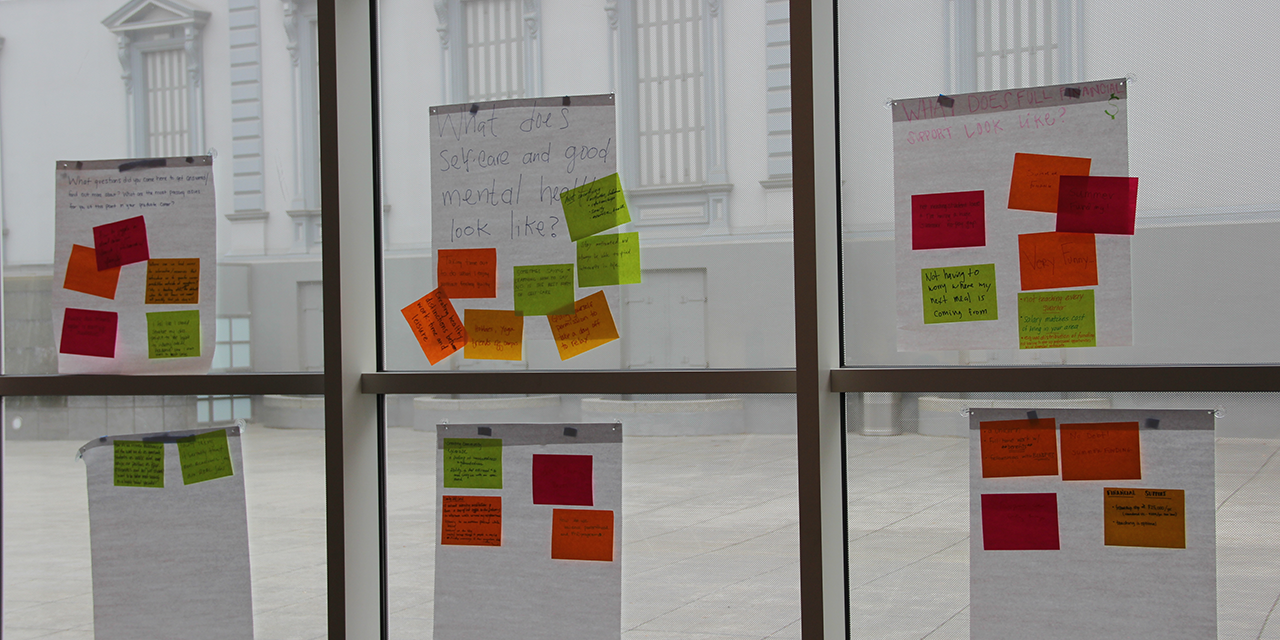

On Monday, November 9th, I attended “Humanists@Work,” a day-long graduate student career workshop at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. Organized by the UC Humanities Research Initiative (UCHRI), the workshop is part of a UC-wide initiative geared towards UC humanities and humanistic social science graduate students interested in careers outside or alongside the academy.

While the workshop was both practically useful—in terms of advice and information gathering—and reassuring about the prospects for graduate students beyond the academy, the day’s conversations often turned to how much progress still needs to be made within the academy, to support graduate students’ needs and goals.

In particular, it was verbally acknowledged throughout the day that not a single faculty member from UC Davis—the nearest UC campus—or from any other UC campuses had shown up to the event, even though faculty were invited to attend. While organizations like the UCHRI are working hard to strengthen graduate career support on UC campuses, it is well understood among the graduate student community that students are receiving little career support from UC faculty—in terms of discussing changes to the career culture within their graduate programs to face new labor realities.

Graduate students are still expected, by and large, to obtain a tenure-track position upon completing their degree, and when they do not or cannot, faculty members often see this as a failure—without confronting the factors that led to it. This cultural problem persists while tenure-track positions are becoming ever scarcer, and graduate students are becoming more resistant to the sacrifices that pursuing a tenure-track position now demands (for example, financial, geographic, and familial sacrifices).

It has been my experience that, even if faculty members say that they support alternative career paths for the students in their graduate program, those faculty do little if anything to actively engage the issue and start changing the culture within their program–or even make their voices heard in debates about issue. A faculty member may tell a student individually that they support their career goals, and they may speak about the academic labor crisis in closed-door faculty meetings, but so far graduate students are not witnessing any substantive changes to their program’s career culture, or open discussions in departments about the complexities of the problem.

Faculty are mostly unengaged with labor issues on campus that do not directly involve them: they often know very little about the actual labor experience of graduate students on campus, and they are resistant to mentoring graduate students for any career other than a R1 faculty position—something the majority of their students will never obtain.

I understand that faculty are under tremendous pressure to successfully balance research, teaching, and service. In one sense, adding alternative career mentorship to this workload only exacerbates and enables the increasingly exploitative nature of the academic labor system. I know from talking to faculty that they feel ill-equipped for alternative career mentoring; they also feel that it conflicts with the purpose of the graduate degree—particularly if that degree is the terminal research Ph.D. I believe that most faculty and graduate students agree that this is a very complicated issue, and a great deal is at stake for everyone involved.

That said, faculty members are in an undeniable position of power and privilege in relation to graduate students, and they have clear responsibilities that are being neglected. While graduate students come and go, faculty members remain and are the source of culture creation within their graduate programs. Faculty admit graduate students into their programs, and when they do they become responsible for the career training of those graduate students—whether they like to think about it that way or not. If the degree is training for a position that most students will never obtain, the degree needs to change. That, or faculty need to mobilize around addressing the vanishing of tenure-track positions.

When graduate programs ignore the actual realities of the graduate career training process, they can do serious damage to people’s lives. They also damage the life of their field. When faculty fail, again and again, to show up for important conversations about the realities of graduate student careers, they perpetuate the widening gulf between the graduate student experience and their own. Graduate students need the faculty to show up for them, to listen to them, and to advocate for them.

As a graduate student, I call upon graduate programs to create more opportunities for open dialogue between faculty and graduate students about these issues. I call upon faculty members to show up, listen, and get involved. I know that many faculty members have opinions about these issues that are different from, and more nuanced than, my own. I am simply calling for more open discussion, with a variety of voices participating in that discussion.

UCHRI, our Office of Graduate Studies, and the UC Davis Humanities Institute each invite faculty interest and involvement in the conversation about the changing realities of graduate student careers. The “Humanists@Work” event was part of a series of workshops that UCHRI will continue to organize on UC campuses across the state, with Los Angeles its next stop in spring 2016. Everyone believes that more faculty attendance is necessary to furthering the goals of the program. DHI, for its part, will continue to offer career development programming through its PhD Unlimited series and hopes to see more faculty at events in the future.